Visualizing Disease States: A COVID-19 Experience

- John Putzke

- Nov 3, 2020

- 9 min read

Updated: Dec 15, 2021

Part III

Summary:

The COVID-19 pandemic has mobilized all areas of research in an effort to minimize its affects. This article examines data reporting techniques designed as a staff incentive for accurate and timely data entry into an international COVID-19 registry of patients admitted to intensive care units (see here). These techniques were incorporated into real-time reports. The strength of the incentive was directly attributable to how well the report transforms data into useful and actionable information that can be leveraged in day-to-day operations. That is, staff are much more likely to enter and keep data up-to-date if it helps make their clinical work easier.

Framing the Effort

An international registry of COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care units (ICU) was designed to gather treatment and outcome-related insights into disease management. Additional information about the registry design and data definition can be found here. Briefly, all those admitted to the ICU diagnosed with COVID-19 were included and assessed daily for up to 28 days. The participating sites represented a broad mix of geographic regions, rural and urban catchment areas. The registry initially included sites located in Italy and China, and was subsequently adopted by the American Society of Anesthesia Research committee on Critical Care Medicine and deployed in multiple medical centers across the United States.

The content domains included the following:

Demographics

Patient Characteristics

COVID-19 Diagnosis Information

Respiratory Function

Arterial Blood Gases

Hemodynamics

Echocardiography

Therapy

Labs

ICU Care

Rescue strategies

iNO Response

Chest x-Ray

Outcome Measures

APACHE II (Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation II)

SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment)

At the time of writing this article, data collection is ongoing during a period of intense time demands on clinical staff, highlighting the need to extract as much practical utility from the data as possible to justify the effort. An important component in response to this need was the development of on-demand reports containing dynamic content directly related to clinic metrics and decision making.

Said differently, researchers always get excited about registry databases, but the practical implications of the added work burden often receives little or no attention. As a result, there is an increased risk of missing, incomplete or inaccurate data, and/or data entry delay. Ensuring all stakeholders, ideally including the patients themselves (e.g., via a web-based portal), experience a significant return on investment is a critical step toward maximizing the utility of the registry. On-demand reporting is an important way to address this concern, particularly report content based on analytical logic that targets the interests of specific stakeholders.

Two types of reports were designed representing two different levels of analysis. Clinical Reports contained data at the individual patient level, and Administrative Reports aggregated data across patients at the organizational / site level. Both reports utilized automated analysis and integrated logic to maximize the utility of the information presented. Since there was a need to rapidly deploy multiple sites and associated users, User Reports were also designed to facilitate the new-user startup process .

Clinical Reports

Data used by Clinical Reports come from a single patient. The visualization techniques used for the COVID-19 registry are described below. Other clinical report and disease visualization techniques can be found it other blog posts here.

Graphs:

Graphs are a common and compelling disease visualization technique. Indeed, the first section of the clinical report displayed domain specific graphs showing daily variable values (see examples below). Graph variables were selected based on conceptual relationships and arithmetic properties, ideally trying to minimize the need for more than one y-axis (e.g., similar range) while not over-complicating the graph with too many variables. In some cases, a single graph was thought to reasonably support a larger number of variables after standardizing values along a common metric (e.g., standard score).

Dynamic Tables:

A tabular row/column display is a common mechanism used to display variable values over time. This approach is particularly helpful when there is a large number of variables with discrepant units of measurement (i.e., a case poorly handled by graphs). Below is an example of a traditional table using ‘Last ICU Temperature.’

Dynamic Tables enhance this traditional design by adding the ability to control display attributes using the values of variables or arithmetic expression. The basics of this approach is similar to ‘conditional formatting’ found in spreadsheet applications. However, each cell (e.g., ‘Day 1’ temperature) is best conceptualized as a web page, thus common spreadsheet constraints do not apply (e.g., one value per cell) . Indeed, anything that can be done on the web can be made to conditionally display within the cell, the contents of which is directly driven by registry data. This combination sets up all kinds of exciting possibilities.

In the current iteration of Dynamic Tables, there is support for control of the following five attributes / display characteristics:

Label font and/or background color

Display of up to four variable values

Cell background color

Cell border color

Conditional images

i.e., The result of an expression and/or a variable value determines which image appears.

Looking again at ‘Last ICU Temperature,’ the example below shows one possible configuration using each of the four options. More specifically:

The label is red (e.g., based on a initial treatment variable value)

The temperature value is displayed

The temperature value sets the background color

The FiO2 value sets the border color

A yellow circle appears if the patient is intubated

To demonstrate what’s happening ‘under-the-hood,’ the configuration below shows all the values within each cell used to set the display options. The top number is the main display variable value (i.e., temperature), the next number controls the background color (i.e., also temperature), the next number controls the border color (i.e., Fraction of Inspired Oxygen [FiO2 %]), and the last number determines which image to display (i.e., a yellow circle if patient is intubated). Note that coded nominal and ordinal level variable values (e.g., intubated: 0 = ‘No’, 1 = ‘Yes’) can be displayed as either text or numbers.

The label font / background color works slightly differently as it is not necessarily based on variable values from a given study visit. It is derived from an arithmetic expression that can be from any combination of values at any visit, the most common being values at the First and Last visit. The current example is based on whether or not the patient presented with prior treatment for temperature.

Cell display characteristics are derived by the value of the variable or by the results of an arithmetic expression. Any expression can be created and used or a predefined expression may be selected including:

Change in variable value

From initial/baseline visit

From previous visit

Percent change in variable value

From initial/baseline visit

From previous visit

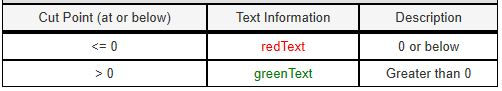

The variable value or expression results are compared against lookup tables to determine the appropriate display setting. The lookup tables can be as granular as needed depending on what’s considered useful within a given clinical/research setting. For example, the lookup tables below determine the cell background color for the ‘Last ICU Temperature’ and ‘PaCO2/FiO2 ratio.’ Note the user is also able to set the text color to use with the background color. For those with a programming interest, the ‘Background Information’ and ‘Text Color CSS’ columns represent the CSS class to use within the appropriate HTML tag.

Last ICU Temperature (celsius)

PaCO2/FiO2 ratio

The lookup tables below show the same approach is used to set the border color and to select which image to display (note: text color is not relevant to these these attributes).

Taken together, Dynamic Tables offer considerable setup flexibility and can be leveraged to help staff quickly and accurately comprehend clinic metrics and/or the presence of data-related signals based on decision logic. To help generate setup ideas, consider some other examples based on different key concerns:

Variable value change and/or event presence

Low/High outlier identification (note: label font color based on last available variable value)

Note also that the data doesn’t have to be patient clinical metrics, but instead related to clinical workflow, staffing responsibilities or other processes. For instance, the table below is used during case conference to indicate needed staff discussion areas (using an Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis [ALS] example).

Summary Tables

There are a number of cases that are poorly suited for the display of data points over time, either using graphs or Dynamic Tables. For instance, cases where the main emphasis is on the most recent variable values and/or where there are a large number of visits and associated variable values. Consider the overwhelming nature of the volume of longitudinal tables and graphs needed to display a single case in a cancer registry (see image of visits below).

Summary Tables provide a mechanism to address this issue. The table was designed to:

Emphasize

Current variable values and percent change

Data collection timing (i.e., how recent is the data from the report date?)

Reduce report space compared to listing all longitudinal data points

Minimize user effort to obtain a snapshot of the patient’s current clinical metrics:

Leverage visual display characteristics to convey meaning

Reduce eye movements

Align variable labels and most recent values

Shift historical information to the right for access on an as-needed basis

Provide common variable value summary statistics

Assess data collection efforts

Each row in the Summary Table contains a variable along with a series of summary characteristics in the columns. The variables are typically separated by domain. Selected items from two domains are shown below.

As a description of the various columns:

Name:

Variable name.

Most Recent — Date (days ago)

The most recent variable value, the date obtained and days from report date.

% Change From Initial / Previous

Percentage change from the initial and previous visit. The font color lookup table can be as granular as needed and each variable can have its own font color lookup table. For example, the clinical significance a 10% change over three days is different for weight vs. white blood cell count.

Initial Value Date (days ago)

The initial variable value, the date obtained and days from report date.

Previous Date (days ago)

The previous variable value, the date obtained and days from report date.

Min / Max (Mean), (Observation Info)

The variable’s minimum, maximum and mean, and the number of times the variable value was entered and the total number of times it could have been entered.

Units

Variable value unit of measurement

Comp %

Completion percentage (based on ‘Observation info’)

Summary Tables leverage the same configurable display attributes set via lookup tables as described in the Dynamic Tables section above. Summary Tables add the font color attribute for the column titled, ‘% Change From Initial / Previous.’ Font color is set using lookup tables that work in a similar manner those used for setting other attributes (see below).

Administrative Reports

Aggregate reporting of COVID-19 cases was an important administrative aim of all institutions participating in the international registry. Thus, on-demand institution-level reports were created. These reports were also used as an initial assessment of treatment strategy effectiveness. Thus, summary of treatment use and response was an important aim. The reports automatically restricted data aggregation to the level of the participating site, users at the data coordinating center (i.e., Massachusetts General Hospital) and others involved in analysis were granted access to all sites.

Selected areas from various reports are presented below as examples of what was set up. To learn about the full functionality available see the Studytrax wiki here.

Enrollment Characteristics

The first set of tables summarized patient characteristics at the time of admission to the ICU. The tables contained demographics, COVID-19 diagnosis status, basic physical and medical characteristics (e.g., height, weight), disease severity (APACHE II, SOFA), and initial values within each outcome domain (e.g., respiratory, hemodynamics, arterial blood gas, lab results).

Day 0, 7, 14, 21, 28 Snapshots

The next set of tables provided weekly summaries using various descriptive statistics. The question answered varied somewhat based on the variable type and descriptive statistic used, this was by design as as this could have been set up however desired. Interval and ratio-level data statistics included only patients remaining in the ICU a given time point. For instance, the mean and standard deviation of respiratory metrics is based on those surviving and remaining in the ICU at a given time point.

Nominal and ordinal level data were summarized in two ways, the first being the same as interval and ratio level data (i.e., only patients remaining in the ICU at a given time point). Dichotomous variables (e.g., yes/no) added cumulative percent (e.g., ‘what proportion of patients were EVER placed on Continuous iv sedation by day 7?’).

Cumulative percent was also used for therapy use.

Scaling Up Operations

The registry experienced considerable expansion over a short period (multiple sites per week), particularly after being adopted by the American Society of Anesthesia Research committee on Critical Care Medicine. Thus, scaling registry operations was an important concern.

User Reports

The essence of the reports described above is a configurable web page that is delivered to users within a secure electronic data capture system (i.e., Studytrax). These reports may contain data driven charts, figures, summary statistics, etc., but may also contain any web-based content. To help onboard new sites and get new users up-and-running as quickly as possible, a “Training Materials” User Report was created and made available upon login. The report served as a repository for related study documents, video tutorials, standard operating procedures, FAQs, etc.

In summary, the combination of using Subject and Administrative-level Reports as a powerful data entry incentive, and User Reports to get new sites and users up-to-speed quickly, served to ensure the successful deployment of the international COVID-19 ICU Registry.

Registry Articles

1: Nozari A, Mukerji S, Vora M, Garcia A, Park A, Flores N, Canelli R, Rodriguez G, Pinciroli R, Nagrebetsky A, Ortega R, Quraishi SA. Postintubation Decline in Oxygen Saturation Index Predicts Mortality in COVID-19: A Retrospective Pilot Study. Crit Care Res Pract. 2021 May 26;2021:6682944. doi: 10.1155/2021/6682944. PMID: 34136282; PMCID: PMC8162249.

2: Bottiroli M, Calini A, Pinciroli R, Mueller A, Siragusa A, Anelli C, Urman RD, Nozari A, Berra L, Mondino M, Fumagalli R. The repurposed use of anesthesia machines to ventilate critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). BMC Anesthesiol. 2021 May 20;21(1):155. doi: 10.1186/s12871-021-01376-9. PMID: 34016056; PMCID: PMC8134805.

3: Ranjeva S, Pinciroli R, Hodell E, Mueller A, Hardin CC, Thompson BT, Berra L. Identifying clinical and biochemical phenotypes in acute respiratory distress syndrome secondary to coronavirus disease-2019. EClinicalMedicine. 2021 Apr;34:100829. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100829. Epub 2021 Apr 15. PMID: 33875978; PMCID: PMC8047387.

Comments